Problem of the Week

Problem A and Solution

The Wandering Cow

Problem

Mme Kennedy lives on a farm with her favourite cow, Mimi. One day, there is a lot of wind and the fence around Mimi’s paddock blows down, so Mimi decides to go exploring.

She leaves at 3:20 p.m. and walks toward the neighbouring farm. It takes her 35 minutes to get there. She visits with her friend Maisie the pig for 18 minutes. Instead of going straight home, she wanders over to a pasture, which is a 26 minute walk. Here she enjoys the delicious green grass and eats for 8 minutes.

At the time Mimi starts eating the grass, Mme Kennedy goes to milk Mimi and notices the broken fence and the missing cow. She hops on her horse, finds Mimi in the pasture, and leads Mimi back to her own paddock. From the time she notices that Mimi was missing, it takes Mme Kennedy 17 minutes to find Mimi and return home.

How long was Mimi gone from her paddock for?

What time did Mimi arrive back at her paddock?

Solution

From the time Mimi left the farm until the time she started eating grass, \(35 + 18 + 26 = 79\) minutes have passed. Note that Mme Kennedy left at the time that Mimi starts eating the grass. So the 8 minutes are included in the 17 minutes of Mme Kennedy travelling. Since it was 17 minutes later that Mme Kennedy returned home with Mimi, then the total time Mimi was gone is \(79 + 17 = 96\) minutes or 1 hour and 36 minutes.

We will look at two different solutions.

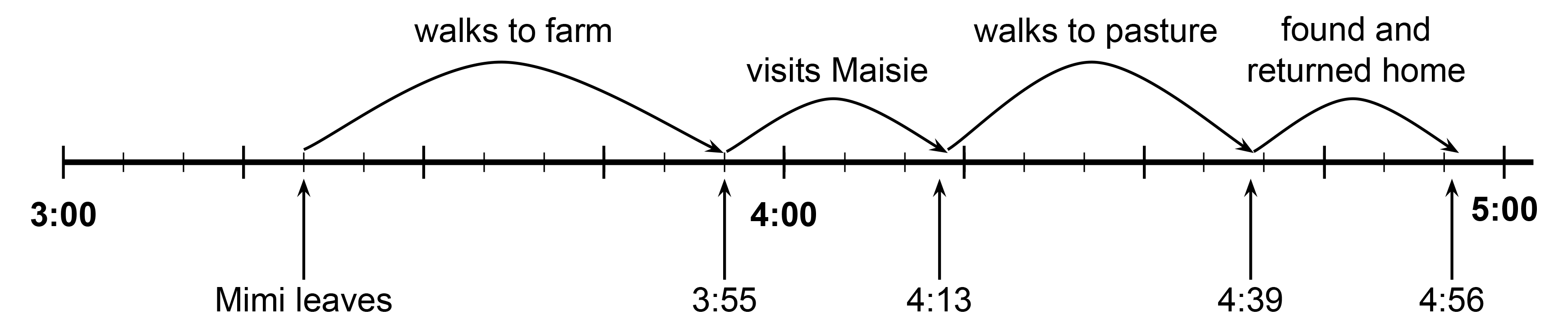

We can make a timeline to track Mimi’s travels:

So Mimi returns home at 4:56 p.m.

We can add the 1 hour and 36 minutes to 3:20. Adding one hour to 3:20 gives 4:20. Adding another 36 minutes gives 4:56.

So Mimi returns home at 4:56 p.m.

Teacher’s Notes

Another way we could solve this problem is to think of time a bit differently. Instead of describing time in hours and minutes, we could think of time as being some number of minutes after midnight. For example 120 would represent 2:00 a.m. since 120 minutes is equal to 2 hours, and 2:00 a.m. is 2 hours after midnight.

Generally we could convert the number of minutes after midnight into a regular time format by calculating the quotient and remainder when we divide the minutes by 60. For example, if we want to know what time it is 785 minutes after midnight, we calculate \(785 \div 60\) which is 13 with a remainder of 5. This means the time is 13 hours and 5 minutes after midnight, which is describing time like a 24 hour clock. This is equal to 1:05 p.m.

Converting from minutes after midnight to a time that we understand seems like a lot of work, so why might we want to represent time this way? The advantage of representing time as minutes after midnight comes when we want to do mathematical calculations with the time such as adding and subtracting. For example, in this problem 3:20 p.m. is 15 hours and 20 minutes after midnight, which is equal to \((15 \times 60) + 20 = 920\) minutes after midnight. Now calculating the time when Mimi returns is a simple addition: \(920 + 35 + 18 + 26 + 17 = 1016\).

When we divide this number by 60 we get 16 with a remainder of 56. This means the time is 16 hours and 56 minutes after midnight, which is 4:56 p.m.

Although the conversion from minutes after midnight to a readable time seems awkward, doing calculations with time is just the same simple addition or subtraction that we do with any whole numbers. This idea of a simple numerical representation of time is basically the way that a computer represents values such as time and other more complex values. Every value in a computer is represented by a sequence of digits. The programs on our computers interpret a sequence and show it in a format that humans can easily read. However, the computer can use the same circuits for calculations on these underlying values even if the values represent very different types of data.

One way to see this yourself is by looking at different formats of a number in a spreadsheet cell. If you type a number like 120781, you can change the format of that number to appear as currency, a percentage, or even a date. In Excel, when you type this number into a cell and then format it as a date, it will appear as Tuesday, September 7, 2230.